Yes anecdotally 20-25% seems impossible, even if everyone under 18 wasn’t susceptible (which isn’t true).How does the professor explain how a Choir in Washington state where 65 of 80 came down with the virus many hospitalized and ~5 died. or the Irish pub in Florida where 15 get infected in one night or the Pharma convention in Boston? There are other events like this as well.

Colleges

- American Athletic

- Atlantic Coast

- Big 12

- Big East

- Big Ten

- Colonial

- Conference USA

- Independents (FBS)

- Junior College

- Mountain West

- Northeast

- Pac-12

- Patriot League

- Pioneer League

- Southeastern

- Sun Belt

- Army

- Charlotte

- East Carolina

- Florida Atlantic

- Memphis

- Navy

- North Texas

- Rice

- South Florida

- Temple

- Tulane

- Tulsa

- UAB

- UTSA

- Boston College

- California

- Clemson

- Duke

- Florida State

- Georgia Tech

- Louisville

- Miami (FL)

- North Carolina

- North Carolina State

- Pittsburgh

- Southern Methodist

- Stanford

- Syracuse

- Virginia

- Virginia Tech

- Wake Forest

- Arizona

- Arizona State

- Baylor

- Brigham Young

- Cincinnati

- Colorado

- Houston

- Iowa State

- Kansas

- Kansas State

- Oklahoma State

- TCU

- Texas Tech

- UCF

- Utah

- West Virginia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Michigan State

- Minnesota

- Nebraska

- Northwestern

- Ohio State

- Oregon

- Penn State

- Purdue

- Rutgers

- UCLA

- USC

- Washington

- Wisconsin

High Schools

- Illinois HS Sports

- Indiana HS Sports

- Iowa HS Sports

- Kansas HS Sports

- Michigan HS Sports

- Minnesota HS Sports

- Missouri HS Sports

- Nebraska HS Sports

- Oklahoma HS Sports

- Texas HS Hoops

- Texas HS Sports

- Wisconsin HS Sports

- Cincinnati HS Sports

- Delaware

- Maryland HS Sports

- New Jersey HS Hoops

- New Jersey HS Sports

- NYC HS Hoops

- Ohio HS Sports

- Pennsylvania HS Sports

- Virginia HS Sports

- West Virginia HS Sports

ADVERTISEMENT

COVID-19 Pandemic: Transmissions, Deaths, Treatments, Vaccines, Interventions and More...

- Thread starter RU848789

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

175 Biogen execs were exposed for two full days, how many tested positive? Not how many cases resulted from it, as each exec went home and spread to family, coworkers and friends.How does the professor explain how a Choir in Washington state where 65 of 80 came down with the virus many hospitalized and ~5 died. or the Irish pub in Florida where 15 get infected in one night or the Pharma convention in Boston? There are other events like this as well.

His term "dark matter" is only used as an analogy meaning we see that some are immune but we have not figured out yet why?It seems reasonable that not everyone is susceptible. Whether you call it "dark matter" or cross reactivity or something else it would explain how three people in a small/moderate sized home of five can test positive while two do not.

#Lag!!!!Minneapolis spiking due to all of the rioting.

Yeh ok 125k are dead in the U.S. precisely because of Trump.....what a moronic statement. Show your work Mika.Good lord.

Rt isn't an "esoteric number". It's a key metric in predicting the rate of future case development. It's up. Spread is increasing. Not by a lot, but it's increasing. Why would you, knowing that, approve a reopening milestone that has proven to increase the infection rate?

Trump thinks like you, which is precisely the reason why we have 125,000 dead people in this country.

Geez I'm looking at AZ dashboard and they are still adjusting daily hospitalization counts three weeks back. Makes me wonder how effective having the testing as planned in late Jan/Feb would have been. No doubt it was needed and would have helped, but even that data would be materially outdated by the time decision-makers had it in determining appropriate actions.I hear you.

My gf who was a nurse hated how much of nursing was paper work , and I think that is certainly part of the problem here. Yet we want quick reporting, we want them doing paper work. Thus the conundrum.

But when I go to the AZ (or name your state)site and I don't actually see up to date(or even close) reporting on certain metrics? Ya, it's lame.

What do you mean by susceptible? Isn’t everyone “susceptible” except maybe young kids? And the thinking is that around 25-35% are asymptomatic but can still spread it?

Here is a summary of Friston's thoughts:

Just one month ago, the idea that most people aren’t susceptible to Covid-19 — perhaps the overwhelming majority — was considered dangerous denialism. It was startling when Nobel-prize-winning scientist Michael Levitt argued in UnHerd at the start of May that the growth curves of the disease were never truly exponential, suggesting that some sort of “prior immunity” must be kicking in very early.

Today, though, the presence of some level of prior resistance and immunity to Covid-19 is fast becoming accepted scientific fact. Results have just been published of a study suggesting that 40%-60% of people who have not been exposed to coronavirus have resistance at the T-cell level from other similar coronaviruses like the common cold.

Now, from the unlikely source of a prominent member of the “Independent SAGE committee”, the group set up by Sir David King to challenge government scientific advice and accused by some of being populated with Left-wing activists, comes a claim that the true portion of people who are not even susceptible to Covid-19 may be as high as 80%.

Professor Karl Friston, like Michael Levitt, is a statistician not a virologist; his expertise is in understanding complex and dynamic biological processes by representing them in mathematical models. Within the neuroscience field he was ranked by Science magazine as the most influential in the world, having invented the now standard “statistical parametric mapping” technique for understanding brain imaging — and for the past months he has been applying his particular method of Bayesian analysis, which he calls “dynamic causal modelling”, to the available Covid-19 data.

Friston referred to some kind of “immunological dark matter” as the only plausible explanation for the huge disparity in results between countries in an interview with the Guardian last weekend. The eye-catching phrase attracted a lot of attention on social media, with some commentators keen to dismiss it as rubbish, but he meant it in a quite precise way: like dark matter, the undetectable substance that makes up approximately 85% of the universe, it is provably there by its effects. We just don’t know anything about it.

His models suggest that the stark difference between outcomes in the UK and Germany, for example, is not primarily an effect of different government actions (such as better testing and earlier lockdowns) but is better explained by intrinsic differences between the populations that make the “susceptible population” in Germany — the group that is vulnerable to Covid-19 — much smaller than in the UK.

As he told me in our interview, even within the UK, the numbers point to the same thing: that the “effective susceptible population” was never 100%, and was at most 50% and probably more like only 20% of the population. He emphasises that the analysis is not yet complete, but “I suspect, once this has been done, it will look like the effective non-susceptible portion of the population will be about 80%. I think that’s what’s going to happen.”

Theories abound as to which factors best explain the huge disparities between countries in the portion of the population that seems resistant or immune — everything from levels of vitamin D to ethnic-genetic and social and geographical differences may come into play — but Professor Friston makes clear that it does not primarily seem to be a function of government coronavirus policy. “Solving that — understanding that source of variation in terms of this non-susceptibility — is going to be the key to understanding the enormous variation between countries,” he said.

Professor Friston is ultra-cautious in his choice of words, and understandably so: the impact of this realisation, if proven correct, is hard to overstate.

Immediately it would change how we should think about lifting lockdown: a tube carriage in London might in theory have to be restricted to 15% capacity to maintain social distancing of 2 metres, but if, as Professor Friston believes, the susceptible population in London was only ever 26% and 80% or more of that group is now provably immune via antibody testing, you can put a lot more people in a tube carriage without increasing the level of risk. Ditto restaurants, pubs, theatres and most recently, MPs in parliament. It would question the whole idea of social distancing being a feature of any “new normal”.

It would take the heat out of the political argument around the pandemic, and give the lie to the idea that it was ever primarily government actions (however incompetent or incompetently executed) that explain differing death rates. As Professor Friston puts it, once you put into the model sensible behaviours that people do anyway such as staying in bed when they are sick, the effect of legal lockdown “literally goes away”.

His explanation for the remarkably similar mortality outcomes in Sweden (no lockdown) and the UK (lockdown) is that “they weren’t actually any different. Because at the end of the day the actual processes that get into the epidemiological dynamics — the actual behaviours, the distancing, was evolutionarily specified by the way we behave when we have an infection.”

Most significantly, it would mean that the principal underlying assumption behind the global shutdowns, typified by the famous Imperial College forecasts — namely, that left unchecked this disease would rapidly pass through the entire population of every country and kill around 1% of those infected, leading to untold millions of deaths worldwide without draconian action — was wrong, out by a large factor. The largest co-ordinated government action in history, forcibly closing down most of the world’s societies with consequences that may last for generations, would have been based on faulty science.

When I put this to Professor Friston, he was the model of collegiate discretion. He said that the presumptions of Neil Ferguson’s models were all correct, “under the qualification that the population they were talking about is much smaller than you might imagine”. In other words, Ferguson was right that around 80% of susceptible people would rapidly become infected, and was right that of those between 0.5% and 1% would die — he just missed the fact that the relevant “susceptible population” was only ever a small portion of people in the UK, and an even smaller portion in countries like Germany and elsewhere. Which rather changes everything.

With such elegant formulations are scientific reputations saved. Practically, it makes not much difference whether, as per Sunetra Gupta, the 40,000 officially-counted coronavirus deaths in the UK are 0.1% of 40 million people infected, or, as per Karl Friston’s theory implies, they are more like 0.5% of 8 million people infected with the remaining 32 million shielded from infection by mysterious “immunological dark material”. If you are exposed to the virus and it is destroyed in your body by mucosal antibodies or T-cells or clever genes so that you never become fully infected and don’t even notice it, should that count as an infection? The effect is the same: 40,000 deaths, not 400,000.

This wouldn’t mean that most of the population is technically immune to Covid-19 — scenarios with a very high viral load, such as doctors treating Covid-19 patients in hospitals may still overpower these defences — but it would mean under normal circumstances, most people would never have contracted the disease.

The atmosphere in the UK continues to change irrespective of Government policy, and if people ever were afraid they are becoming less so, having intuited that, for now at least, the coronavirus threat seems to be in retreat. Gradually, the scientists are providing explanations for why that might be.

23 - if interested, take a look through my two posts from this weekend on this and a third, which has the source to the initial work on this - been talking for a couple of months now about the potential for "cross-reactivity" in the population, i.e., people having some level of immunity to disease A (coronavirus) due to exposure to some other virus (other coronaviruses for example) in the past. Probably 50% of unexposed people have T-cell activity against CV2, despite not having measurable antibodies, based on experiments with small groups of subjects. It's unknown whether this confers none, a little or a lot of immunity for these people, but if it's a lot, that's huge and could provide the scientific underpinnings to the probabilistic modeling Friston has done, which has some holes, as per my 2nd post, linked below. He could be right, but it's far from a given.

This is the link to the article that wisr (one really should cite sources for long quotations, both to help the reader and to protect the site) quotes in his post: https://unherd.com/2020/06/karl-friston-up-to-80-not-even-susceptible-to-covid-19/

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-215#post-4620781

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-216#post-4620885

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-116#post-4563258

#Lag!!!!

Cases are up slightly and tied to reopening bars...

https://www.minnpost.com/health/202...ased-new-cases-some-cases-tied-to-bar-visits/

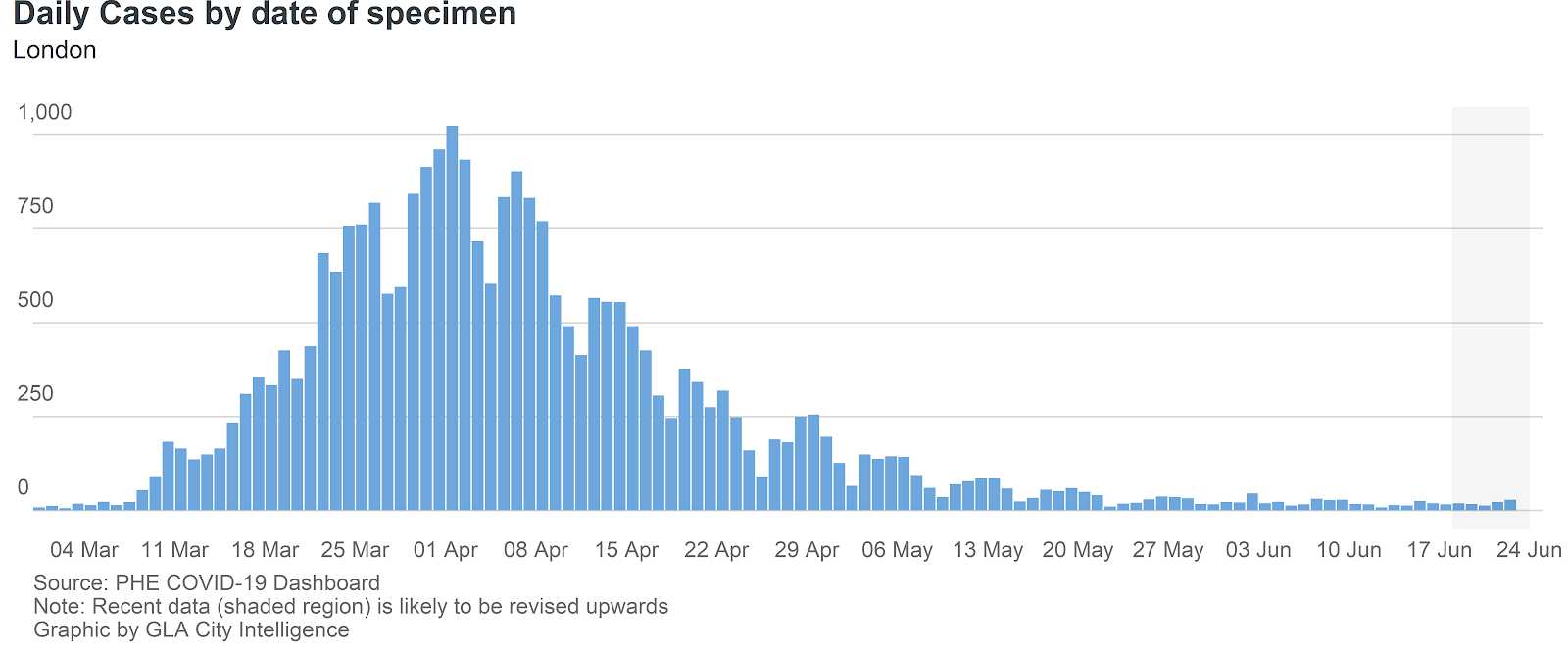

I have doubts about Friston's speculation of 20%, but from looking at the spread in locations that were hard and early I would not be surprised if that number was between 30 and 50%. London has reopened schools and some shops for the month of June. So although it is not business as usual, it is not locked down. They have just under 600 total cases in London between 6/5 and today...averaging around 20-25 per day. That is in a city of 9million.23 - if interested, take a look through my two posts from this weekend on this and a third, which has the source to the initial work on this - been talking for a couple of months now about the potential for "cross-reactivity" in the population, i.e., people having some level of immunity to disease A (coronavirus) due to exposure to some other virus (other coronaviruses for example) in the past. Probably 50% of unexposed people have T-cell activity against CV2, despite not having measurable antibodies, based on experiments with small groups of subjects. It's unknown whether this confers none, a little or a lot of immunity for these people, but if it's a lot, that's huge and could provide the scientific underpinnings to the probabilistic modeling Friston has done, which has some holes, as per my 2nd post, linked below. He could be right, but it's far from a given.

This is the link to the article that wisr (one really should cite sources for long quotations, both to help the reader and to protect the site) quotes in his post: https://unherd.com/2020/06/karl-friston-up-to-80-not-even-susceptible-to-covid-19/

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-215#post-4620781

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-216#post-4620885

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-116#post-4563258

Fascinating, thank you so much, and to wisr as well.23 - if interested, take a look through my two posts from this weekend on this and a third, which has the source to the initial work on this - been talking for a couple of months now about the potential for "cross-reactivity" in the population, i.e., people having some level of immunity to disease A (coronavirus) due to exposure to some other virus (other coronaviruses for example) in the past. Probably 50% of unexposed people have T-cell activity against CV2, despite not having measurable antibodies, based on experiments with small groups of subjects. It's unknown whether this confers none, a little or a lot of immunity for these people, but if it's a lot, that's huge and could provide the scientific underpinnings to the probabilistic modeling Friston has done, which has some holes, as per my 2nd post, linked below. He could be right, but it's far from a given.

This is the link to the article that wisr (one really should cite sources for long quotations, both to help the reader and to protect the site) quotes in his post: https://unherd.com/2020/06/karl-friston-up-to-80-not-even-susceptible-to-covid-19/

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-215#post-4620781

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-216#post-4620885

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-116#post-4563258

I have doubts about Friston's speculation of 20%, but from looking at the spread in locations that were hard and early I would not be surprised if that number was between 30 and 50%. London has reopened schools and some shops for the month of June. So although it is not business as usual, it is not locked down. They have just under 600 total cases in London between 6/5 and today...averaging around 20-25 per day. That is in a city of 9million.

As I said back in May, when cross-reactivity was discovered, answering the question of what it means at a population scale for potential immunity (either not getting infected or at worst having mild cases) and who might and might not get infected is possibly the biggest scientific question we have right now, since if only 20-25% will ever be impacted vs. 55-80% (if the herd immunity estimates most believe in are correct), that's a ginormous difference in potential deaths/serious illnesses. At 20%, we're talking 330-660K US deaths, eventually, assuming an infection fatality rate of 0.5-1.0% (which is a pretty solid number now that we have antibody-population testing), while at 60% infected, it's 990-1980K US deaths eventually (assuming no interventions to reduce spread or any cure/vaccine/virus weakening - which are all unrealistic, but we're talking potential worst case). It's just huge. I wish I knew the answer.

In before the lock!!!Yeh ok 125k are dead in the U.S. precisely because of Trump.....what a moronic statement. Show your work Mika.

Hope not--this thread is very informative for the most part, sometimes it's iron sharpening iron :Sly:... but not out-of-control. Ignorant political cheap shots like 4real's are relatively far and few between, but no reason to be ignored if the mods allow them in the first place.In before the lock!!!

Cases are up slightly and tied to reopening bars...

https://www.minnpost.com/health/202...ased-new-cases-some-cases-tied-to-bar-visits/

Yep, you can link every case to the bars in Minnesota.

[roll]

Yeh ok 125k are dead in the U.S. precisely because of Trump.....what a moronic statement. Show your work Mika.

Morons say moronic things.

Whoever said I have on ignore, which nutjob I wonder.

4real.Morons say moronic things.

Whoever said I have on ignore, which nutjob I wonder.

Thanks looked familiar just have not been there in a while couldn't pinpoint itDonovan's Reef in Sea Bright

Ah, G4 , right in time before the election.

How convenient, no wonder why CNN and the NYT are pushing this.

How convenient, no wonder why CNN and the NYT are pushing this.

I didn't miss what he was trying to suggest. I'm just not a believer of it.I think you missed the whole point of what Friston's model suggests. We will use London as an example. London has slowly begun reopening since last month. Effective June 1st schools opened and some shops, etc. I understand it has been a partial reopening but happening nonetheless. Antibody testing has shown that 17% of Londoners have had the disease by May 22nd. Friston's model suggests that roughly 20-25% of people are actually susceptible meaning that they are approaching herd immunity in the susceptible population.

What have we seen as they slowly reopen?

Either you want to believe that they are incredible at social distancing/mask wearing and have avoided a spike or you can be open to the POSSIBILITY that there susceptible population has been reduced to the point where the virus is struggling to spread. I guess time will tell.

When I first read his thoughts and suggestions based on his model, I thought yeah right. But the data we have seen in London, NYC, NJ, etc seem to agree. If we reopen and things spike like Florida then he is wrong. But if not and he is right then we are not handling things correctly in areas already burned up by the virus.

I'm a much bigger believer in masks and outdoor activities. Moreso the former.

I suspect scenes like we saw from the outdoor bars in NJ will cause a jump. Maybe the outdoor aspect keeps the #'s down but If we open indoor bars prior to a vaccine, I would certainly expect a jump.

Which is a very true statement.The Godfather just said there's no guarantee of a vaccine by early 2021.

The curves are now showing what many figured would be the case. Cases go up, hospitalizations follow soon after, and deaths follow soon after that.

So that debate should be settled.

What to look for now is, can the hospital systems, thanks to new treatments, and thanks to catching cases earlier,(and maybe the weakening of the virus or the lowering of viral load) stand up to the growing case #'s? And can they keep the death #'s to an acceptable level?

So that debate should be settled.

What to look for now is, can the hospital systems, thanks to new treatments, and thanks to catching cases earlier,(and maybe the weakening of the virus or the lowering of viral load) stand up to the growing case #'s? And can they keep the death #'s to an acceptable level?

I would guess that asking anyone if they rioted or protested would be considered politically incorrect re: tracing, and I have my doubts a person would volunteer that information. So yeh, agreed this news report should be taken with a grain of salt.Yep, you can link every case to the bars in Minnesota.

[roll]

Don't know if this has been mentioned already or not but talking about NYC infection rates etc....from Scott Gottlieb on CNBC.

From the article:

About 25% of New York City-area residents have probably been infected with the coronavirus by now, former Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb told CNBC on Tuesday.

Researchers at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City published a study Monday, which suggested that 19.3% of people in the city had already been exposed to the virus through April 19.

Even if that many people have Covid-19 antibodies in New York City, the initial epicenter of the U.S. outbreak, the researchers noted that would still be well below the estimated 67% needed to achieve herd immunity — which is necessary to give the general public broad protection from the virus. The study has not yet been peer-reviewed nor accepted by an official medical journal for publication.

Based on their findings, the researchers concluded that about 0.7% of everyone infected with the virus in New York City died due to Covid-19.

However, Gottlieb said the infection-fatality rate, which factors in asymptomatic patients who never develop symptoms, has likely risen since mid-April.

The infection-fatality rate is likely lower than the case-fatality rate, which looks at the percent of people who have symptoms and end up dying. Gottlieb said the case-fatality rate might be closer to 1.1% or 1.2%.

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/30/rou...-with-coronavirus-dr-scott-gottlieb-says.html

From the article:

About 25% of New York City-area residents have probably been infected with the coronavirus by now, former Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb told CNBC on Tuesday.

Researchers at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City published a study Monday, which suggested that 19.3% of people in the city had already been exposed to the virus through April 19.

Even if that many people have Covid-19 antibodies in New York City, the initial epicenter of the U.S. outbreak, the researchers noted that would still be well below the estimated 67% needed to achieve herd immunity — which is necessary to give the general public broad protection from the virus. The study has not yet been peer-reviewed nor accepted by an official medical journal for publication.

Based on their findings, the researchers concluded that about 0.7% of everyone infected with the virus in New York City died due to Covid-19.

However, Gottlieb said the infection-fatality rate, which factors in asymptomatic patients who never develop symptoms, has likely risen since mid-April.

The infection-fatality rate is likely lower than the case-fatality rate, which looks at the percent of people who have symptoms and end up dying. Gottlieb said the case-fatality rate might be closer to 1.1% or 1.2%.

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/30/rou...-with-coronavirus-dr-scott-gottlieb-says.html

Can anyone tell me how Rt can be rising if our daily cases have been consistently fluctuating between 300 and 400 for the past two weeks? According to 91-Divoc which sources data from Johns Hopkins, NJ's 7 day moving average of cases has declined from 404 17 days ago to 265 yesterday. How can we be reducing daily cases if Rt is rising?

My supposition is that daily positive cases will decline until Rt is =1, so if the trends of increasing Rt and decreasing daily cases continue, we will bottom out around 200-225 daily positive cases, and then start to increase again if we rise above Rt=1? If that's the case, then do I understand it that Rt is a rate of change, and it's a slowing of the decrease that is visibly manifest?

My supposition is that daily positive cases will decline until Rt is =1, so if the trends of increasing Rt and decreasing daily cases continue, we will bottom out around 200-225 daily positive cases, and then start to increase again if we rise above Rt=1? If that's the case, then do I understand it that Rt is a rate of change, and it's a slowing of the decrease that is visibly manifest?

Don't know if this has been mentioned already or not but talking about NYC infection rates etc....from Scott Gottlieb on CNBC.

From the article:

About 25% of New York City-area residents have probably been infected with the coronavirus by now, former Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb told CNBC on Tuesday.

Researchers at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City published a study Monday, which suggested that 19.3% of people in the city had already been exposed to the virus through April 19.

Even if that many people have Covid-19 antibodies in New York City, the initial epicenter of the U.S. outbreak, the researchers noted that would still be well below the estimated 67% needed to achieve herd immunity — which is necessary to give the general public broad protection from the virus. The study has not yet been peer-reviewed nor accepted by an official medical journal for publication.

Based on their findings, the researchers concluded that about 0.7% of everyone infected with the virus in New York City died due to Covid-19.

However, Gottlieb said the infection-fatality rate, which factors in asymptomatic patients who never develop symptoms, has likely risen since mid-April.

The infection-fatality rate is likely lower than the case-fatality rate, which looks at the percent of people who have symptoms and end up dying. Gottlieb said the case-fatality rate might be closer to 1.1% or 1.2%.

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/30/rou...-with-coronavirus-dr-scott-gottlieb-says.html

Yes, good paper. I actually communicated with one of the authors about how it was good to see alignment with the NYDOH data from back in late April (when the Mt. Sinai study was done). I also suggested that they might want to consider mentioning the ~4000 presumptive NYC deaths at that time (4/19, when there were 11,413 "official" deaths), as that would move the infection fatality rate to about 1% (as of 4/19), as most of those presumptive died in the hospital and were obvious COVID patients, but had no test - in part, because they knew they had COVID and taking the swabs actually endangers the nurses unnecessarily. They also only listed the stay at home order as being on 3/22, but I pointed out that NYC was effectively shut by 3/16 (schools/bars/restaurants and many commuting jobs). He said he'd likely put those comments in the final version.

I also think Gottleib may have been misquoted in saying the CFR might be closer to 1.1-1.2% (think he meant IFR). The CFR right now in NY is 7.6% (Worldometers), 8.1% (JHU) or 6.0% (NYDOH), with the variability being due mostly to the now ~6000 presumptive deaths, which WM/JHU "count" while the NYDOH does not (but they track it). Regardless, all of those are a far cry from 1.1-1.2%, which is what the actual NY State IFR is, counting in the 6000 presumptives. Also, Gottleib's guess of 25% currently infected in NYC could also be a bit high, as the antibody testing from 6/13 by the NYDOH, was only 21.6% (and the DOH/Mt. Sinai #'s were close on 4/19).

I recall reading his stuff awhile back (and Leavitt's - we had a huge exchange on Leavitt's theories back in March in this thread and on the CE board) and being at least intrigued, being a math/probability guy. In fact, if you go back to March/April, I was taking some of their approach and the data from he Diamond Princess (where ~20% became infected) to postulate that the max infected could end up being 20%. But then as things got worse and worse in Europe and the NE US and we saw some populations with 50-80% infections by PCR testing (prisons and meatpacking plants) and then saw 20% in NYC and up to 40-45% in parts of the Bronx (33% overall in the Bronx) by antibody testing, I moved more towards thinking that maybe the 55-80% being infected would be correct.

It was also hard to have high faith in a purely DCM-based (dynamic causal modeling) probabilistic approach to epidemiology for me, without some shred of scientific evidence showing how only 20% or so might truly be affected/infected. But in the last 6 weeks or so, since that first cross-reactivity finding was published (see the link below) in mid-May, I've found it to be at least more plausible, which is why in most of my long-winded sets of calcs of potential deaths, I now put in the caveat about cross-reactivity (and cures/vaccines and virus weakening) potentially greatly reducing infections/deaths, if confirmed.

https://rutgers.forums.rivals.com/t...entions-and-more.191275/page-116#post-4563258

Friston may be confident about all this, but I'm certainly not and until we have hard evidence of actual immunity from cross-reactivity (we don't yet) I think governments still have to plan for 55-80% true infections with an IFR of 0.5-10.%, which means millions of deaths worldwide being at least plausible.

Also, I take exception with his comments about variability in populations - it's hard to think that that could be so large as mean that 20% are "susceptible" (i.e., no "natural immunity" to the virus) in the UK and 33% in the Bronx. The simpler explanation is that people in the Bronx were subject to the most transmission risk, because it's a poorer area, where people often have more public-facing jobs and have to utilized public transit vs., say, Manhattan or SI, which had much lower infection rates (16-17% via antibody testing). But we can't "know" for sure which scenario is correct.

And I think he greatly overlooks the power of masking/social distancing (which are really the same thing, i.e., measures to prevent transmission). If those didn't matter, he needs to find a way to explain why most of the East Asian countries only have 50-250 cases/1MM, while Europe, the US and many others have 2500-10,000 cases/1MM, about 40-50X more (and similarly much greater deaths per 1MM) - most experts believe that masking/distancing are a huge part of why those countries have such low transmission rates. I can't believe that Friston would chalk up the fact that Tokyo only has 0.1% of its population having antibodies vs. the Bronx having 33% with antibodies being due to differences in native immunity; I assume the same will be true in SK, Taiwan and elsewhere in East Asia, but haven't seen antibody test results from those places yet. Meaning he's wrong about distancing/masking and if he's wrong about that, maybe his modeling isn't perfect either.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/06/16/national/science-health/tokyo-coronavirus-antibodies/

Edit: one more point: even if only 20% of 330MM are "susceptible" at 0.5-1.0% IFR, that would still be 330-660K US deaths, which is simply unacceptable, so it doesn't change what we should be doing, IMO, which is universal masking and a much better job of tracing/isolating any positives and contacts of positives. We can do all that without having shutdowns.

Wanted to update this - @RU23 @wisr01 @rutgersguy1 - thought you'd be interested, so here goes. I mentioned some apparently clear exceptions to the 20-25% susceptible to being infected number Friston has been postulating (the Bronx and some small populations like in Lombardy with 40-50% with antibodies). Think I also mentioned prisons/meatpacking plants in some other post, but wanted to get back to that here.

It turns out that the Marion Ohio prison would be very hard to explain via Friston's model. Back in late April it was reported that 2000 of 2500 inmates (80%) tested positive for the coronavirus via viral PCR testing in the largest outbreak anywhere in the US. This clearly says 80% were infected, not 20-25%, although the asymptomatic fraction was 95%, which is very high, perhaps implying some native immunity.

However, here's the bottom line for me: out of those 2000, 13 died (12 inmates and one guard) for an infection fatality ratio of 0.65%, which is square in the middle of the 0.5-1.0% IFR range I've been predicting, as have many others. And itg's 0.65% of 80% infected, not of 20% infected. As per my post above, if only 20% are susceptible to infection (Friston's model) and the IFR is 0.5-1.0%, which is where it is now in NY, based on antibody testing, then 330-660K US deaths could occur eventually, whereas if 80% are susceptible (as appears the case at Marion) and the IFR is still 0.5-1.0% (as it was in Marion), then the US deaths could eventually be 1.32-2.64MM.

Huge difference. Is there something unique about Marion with regard to susceptibility (doubtful, other than R0 is going to be very high in a prison) or death rates (maybe - it's 100% male, 50% black, but the average age is 40 years old - also have no idea which people died - if I were an epidemiologist, I'd want to do a case study on this- could be a factor of 2-3X though, which could bring that IFR down to 0.2-0.3%) that would explain the data or is Friston's model simply wrong and the 55-80% getting infected, based on estimated herd immunity correct? As an aside, it would be interesting to follow these prisoners to see if they have immunity now and to check their antibodies over time. Food for thought, at least.

https://www.propublica.org/article/...00-inmates-it-had-over-2000-coronavirus-cases

https://www.themarshallproject.org/...-outbreaks-could-teach-us-about-herd-immunity

http://ciic.state.oh.us/docs/Marion Correctional Institution 2015.pdf

Last edited:

20% being susceptible really sounds like fairy tale stuff to my ears.

Why did spread stop in NYC? Because they locked it down. Because of masks. Simple as that.

Would this theory apply to the Flu? Or a cold? Or any other virus?

I remember being sick when I was young, but not sure if I ever had the flu. Then through 20 years of adult hood I never had the flu. Did this mean I had dark matter which kept me from getting the flu? Given I did eventually get the flu, obviously not.

That theory makes no sense to me.

Why did spread stop in NYC? Because they locked it down. Because of masks. Simple as that.

Would this theory apply to the Flu? Or a cold? Or any other virus?

I remember being sick when I was young, but not sure if I ever had the flu. Then through 20 years of adult hood I never had the flu. Did this mean I had dark matter which kept me from getting the flu? Given I did eventually get the flu, obviously not.

That theory makes no sense to me.

Well they did.Nope. You said FL cases were trending up before June 5th. Not really. They sure trended up after June 5th.

NJ started stage 1 re-opening on May 18th. Six weeks later we had 156 cases reported today.

Did they go up significantly after indoor bars opened? Yes.

The "dark matter" is just a term, since Friston didn't have a scientific explanation - cross-reactivity is a possible scientific explanation for a good sized portion of people having native immunity. It's why we truly, truly need a scientific answer to this, but I've read it could take months and until then we'll all be wondering and bickering. I struggle with believing the 20-25% number based moreso on parts of the Bronx having 40+% infected, as that wasn't some "experiment" in the very close quarters of a prison.20% being susceptible really sounds like fairy tale stuff to my ears.

Why did spread stop in NYC? Because they locked it down. Because of masks. Simple as that.

Would this theory apply to the Flu? Or a cold? Or any other virus?

I remember being sick when I was young, but not sure if I ever had the flu. Then through 20 years of adult hood I never had the flu. Did this mean I had dark matter which kept me from getting the flu? Given I did eventually get the flu, obviously not.

That theory makes no sense to me.

His term "dark matter" is only used as an analogy meaning we see that some are immune but we have not figured out yet why?

We don’t know what dark matter is. We know it’s there because galaxies would not be held together without it. Like a “singularity”, a word that says we don’t know what it is.

So according to the CDC you can have a positive antibody if you had the common cold? How inaccurate is that. I had a cold in the last few months so I may test positive. Seems nobody has a clue about this yet.

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/testing/serology-overview.html

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/testing/serology-overview.html

Well they did.

Did they go up significantly after indoor bars opened? Yes.

what about deaths...our daily deaths continue to go down although some keep waiting for them to go up dramatically

also with the spikes i am seeing on the worldometer in certain states, no one can tell me that protests are not part of that. There I said and the media should be saying it too. If we are going to slam red state openings we cannot ignore protests that started a month ago and have had varying levels....there were gay pride rallies across the country over the past weekend that had plenty of pictures of maskless attendees

gov Murphy tweeted about if the measures save just one life then its worth it but omg how can he say that while encouraging those protests which of course there had to be spread, that is common sense, mask or no mask...and I am not making this poltical. Its about hypocrisy..

another thing i wonder about are college athletes who are able to work in gyms while the average person cannot..why...why are college athletes given a special privilege to do this and I am assuming professional athletes are able to use gyms in prep for upcoming seasons

gov Murphy tweeted about if the measures save just one life then its worth it but omg how can he say that while encouraging those protests which of course there had to be spread, that is common sense, mask or no mask...and I am not making this poltical. Its about hypocrisy..

another thing i wonder about are college athletes who are able to work in gyms while the average person cannot..why...why are college athletes given a special privilege to do this and I am assuming professional athletes are able to use gyms in prep for upcoming seasons

also with the spikes i am seeing on the worldometer in certain states, no one can tell me that protests are not part of that. There I said and the media should be saying it too. If we are going to slam red state openings we cannot ignore protests that started a month ago and have had varying levels....there were gay pride rallies across the country over the past weekend that had plenty of pictures of maskless attendees

We don't need the media to tell us what we know to be true.

What?? That is not true for most antibody tests which are looking for a very specific antibody related to Covid 19. We all have antibodies of something.So according to the CDC you can have a positive antibody if you had the common cold? How inaccurate is that. I had a cold in the last few months so I may test positive. Seems nobody has a clue about this yet.

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/testing/serology-overview.html

what about deaths...our daily deaths continue to go down although some keep waiting for them to go up dramatically

The overall fatality trends in the country have come down because the states that were hit hard early have seen there deaths decrease significantly from untenable numbers, but that should not be seen as a sign that current case increases will not lead to an increase in deaths.

Check the deaths of states that have had recent spikes in cases, they are trending upward.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 93

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 34

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 488

- Views

- 24K

- Replies

- 98

- Views

- 3K

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT